Despite the name of this newsletter, I must confess that I don’t read much poetry.

I’m not sure why. Poetry should very much be my kind of shit. I like rap, which is how teachers try to convince you that poetry is cool. I’ve performed on stage what could be loosely considered poetry. My first foray into writing was, technically, poetry, and I’ve continued to come back to it throughout my life.

In fact, my first publication was a statewide writing competition in the poetry category (I did my best 2-Pac impression and was an honorable mention).

What I’m saying is I should like poetry, and I guess I do but I also can’t really say that because I simply don’t read much of it.

Poetry is intimidating. I often feel like I don’t “get” it. I don’t even know what it means to “get” something you read. To me it’s not just a synonym for “understand,” though comprehension can be part of it. Getting it also includes a level of enjoyment, appreciation, or at least recognition of what the poet is attempting to do on the page, beyond just identifying a theme or whatever. All of those stem from understanding but also exceed it.

I want to get poetry better, so I called on some poets to help me out.

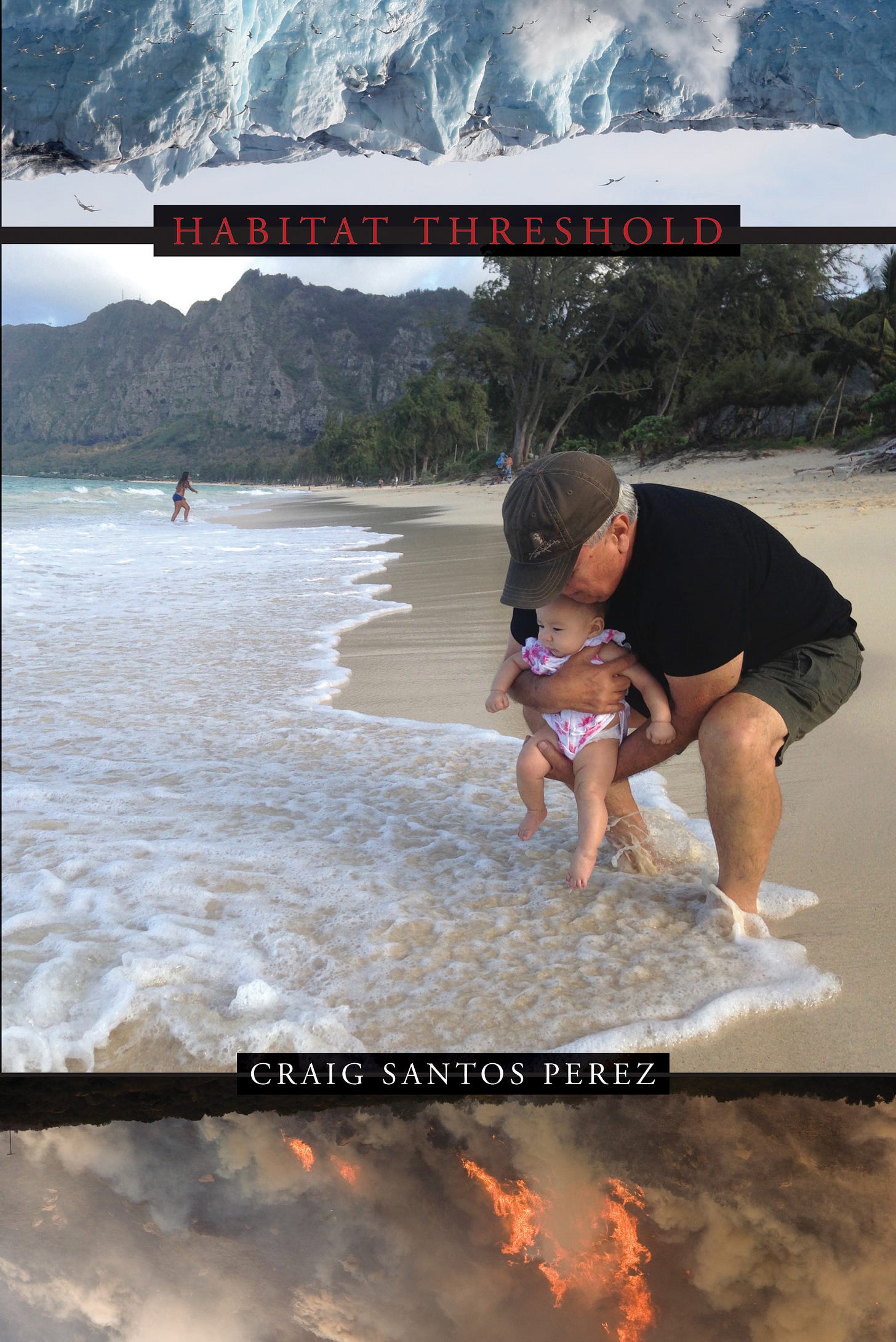

Brett Ortler is the author of Lessons of the Dead, which I read and greatly enjoyed last year; Brian Glaser is the author of Contradictions, which I also read and enjoyed last year; and Craig Santos Perez, whose book Habitat Threshold I have not yet read but is on my list for this year. All three of them are talented and prolific and generous beyond my descriptions here, so I’ll leave a more complete bio for each at the end. Do check out their stuff.

For the sake of space, some of the questions I asked aren’t included and some of the responses have been shortened, but I will post the full Q and A in a separate post.

1. What made you start reading poetry?

BO: While I’d read some poetry as a kid—especially Shel Silverstein and collections of light verse for kids—I didn’t start reading poetry more seriously until I was in high school. I remember coming across a Dover Thrift Editions of 100 Best Loved Poems and being struck by a number of the poems, but especially “She Walks in Beauty” by Lord Byron. The sound of it was what really struck me, especially the first stanza.

BG: My first encounter was with poets, something in the rhythms and images of Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson. These were books of our family library. I had an idea that their inner lives were really intense, as I felt mine was, and that they made something beautiful out of what Frost calls their inner weather. I wanted to do that, too. So I would say I first read poets, not poetry or poems. Frost and Dickinson.

CSP: I started reading poetry in high school because I had inspiring teachers. I started writing poetry because it was a creative and fun way to express myself.

2. As a writer, what does poetry offer you that prose does not or cannot?

BO: It’s easier to invent a world or immerse your reader in a character/story/setting in prose than in poetry. Poetry is best-suited for the interior and revelatory: if there’s any way to succinctly transfer the immediacy of an emotion or an experience or an epiphany, it’s poetry.

BG: I think often of something one of my teachers, Brenda Hillman, said about writing poems. Don’t lie, she said. In fiction, you have to lie, deliberately. At least that’s how I look at it. It’s hard for me to read fiction for long—I’m right there until the lying starts, and that’s where the poetry ends.

CSP: Poetry offers me a more interesting and unique way to engage with language and all its expressive, artistic, and musical capacities.

3. Why do you think people don’t read as much poetry as they do novels or nonfiction?

BO: Part of this is no doubt because of poetry’s reputation—difficult, esoteric, seemingly out-of-date and out-of-touch. What most folks know of poetry is also pretty technical (rhyme, sonnets, meter). I think it’s a disservice that we start out by teaching formal poetry to kids, as it defines the genre early on as confusing and frustrating. It’s like showing someone the math behind the Uncertainty Principle as an introduction to physics. It can scare folks off, and that in turn can lead them to avoid reading it. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read a poem aloud at a reading (mine or someone else’s) and someone responded, “I didn’t know you could do that in a poem,” as if the poem was breaking some hidden taboo of literature.

BG: I have no idea why. Poetry has a passionate and brilliant subculture, but almost no place in the mainstream. One possibility is that making poetry doesn’t square with our culture’s imperative to maximize our human capital. I think of something Seamus Heaney said in his Nobel Prize lecture. What “always will be to poetry's credit,” he wrote, is “the power to persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it.”

CSP: Fiction and nonfiction books often sell more copies than books of poetry, but there are some forms of poetry that are more widely read, including Instagram poetry, poetry memes, spoken word poetry videos, and celebrity poetry (such as Amanda Gorman, Rupi Kaur, and Maya Angelou).

4. What do you say to someone who is hesitant to read poetry because they fear they won’t or don’t “get” it?

BO: The writer sets the table, but the reader brings the meaning. Don’t be ashamed of your interpretation of a poem, or if it differs from those of others, and especially for your own taste in poetry. If you don’t like something, try something else. Happily, there are so many wonderful poets writing today—and with so many different styles/approaches—that there certainly is work around that most folks would enjoy.

BG: One of the great inventions of the twentieth century was Sigmund Freud’s idea of free association. It’s the opposite of mindfulness—instead of detaching from your thoughts, pay hyper close attention to them and how they lead from one to another. When you hear a poem, free associate to it. Let your mind roam in response to the language.

CSP: I would say to read poetry about topics you are interested in and seek out poets from a similar age group, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc, that you can relate to.

5. If someone is interested in reading more poetry but doesn’t know where to start, what are your recommendations?

BO: Read as widely as you can. I mean that in terms of styles, movements, and so on. Be aware that a lot of the older anthologies—the ones I grew up on—are mostly lily-white and consist of male writers. So absolutely diversify your reading lists. One of my favorite things to do is head to the library or a bookstore and simply browse. Pull off a handful of books and dig in. That’ll help you get your bearings, and it’s a great way to find some new favorite authors.

BG: Read poetry in translation. There is a journal called Modern Poetry in Translation and for less than a hundred dollars you can access an archive that can sustain you for months. And there are at least two international anthologies still in print: The Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry and The Ecco Anthology of International Poetry.

CSP: I would start by subscribing to the Academy of American Poets Poem-a-Day series because then you receive a free poem everyday from a diverse range of poets.

Brian Glaser is the author of Difficult Joy (Shanti Arts, 2021) and other books. He is a Professor of English at Chapman University in Orange, California.

Brett Ortler is the author of Lessons of the Dead (Fomite, 2019), and the co-editor/founder of Knockout Literary Magazine and Left Hooks. He is the author of a number of popular science books, including Backyard Science & Discovery Workbook: Midwest.

Craig Santos Perez is a Professor of English at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He is the author of Navigating CHamoru Poetry (University of Arizona Press, 2022) and other books.

January Reads

Rejection gave me a fresh start, a new year by Jami Attenburg, The Guardian

The Hanya Yanagihara Principle by Andrea Long Chu, Vulture

From Quixotic To Kafkaesque: Where We Stand One Week Into The Standoff Between Novak Djokovic And The Australian Government by Steve Tignor, Tennis.com

The Cold War Killed Cannabis As We Knew It. Can It Rise Again? by Casey Taylor, Defector

Men Should Use More Exclamation Points!!! by Magdalene Taylor, MEL Magazine

They bought a blender. Three weeks later, their cats continue to hold it hostage by Dawn Fallik, The Washington Post

I also enjoyed this back and forth then back again that started in December when Heather Havrilesky published an excerpt from her forthcoming memoir in the New York Times entitled “Marriage Requires Amnesia.” This prompted Albert Burneko from Defector to respond with “Maybe Your Marriage Just Sucks!” Burneko’s piece compelled Kate Harding to respond to his response with “Have We Forgotten How to Read Critically?” in Dame Magazine. They are all interesting, insightful and evocative pieces of writing on their own merits.

January Books

“When people like Percy die, then part of what makes Hawaiʻi a unique place, a local place, also dies.”

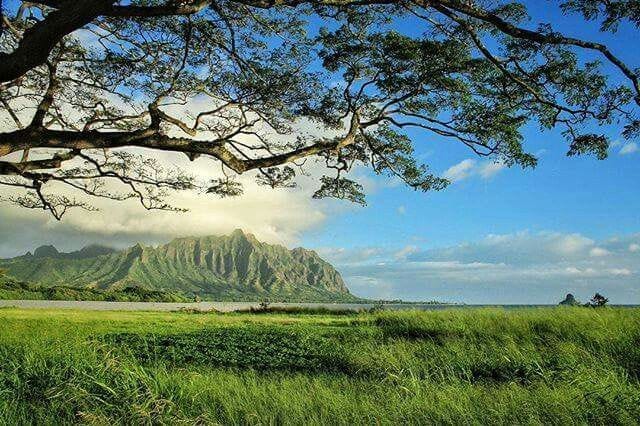

Daiki, meaning “big happiness” in Japanese, was the sumo name given to Percy Kipapa. He grew up tucked against the rugged Koʻolau mountains in the rural community of Waiāhole. That name is important. Waiāhole is where he was from, and it was also who he was.

The people of Waiāhole fought wealthy land developers and actually won, holding on just a little longer to a lifestyle of Hawaiʻi that is all but certain to perish. Kipapa embodied that fighting spirit, working his way from the bottom of the brutally hierarchical world of professional sumo into its top divisions.

Waiāhole was also a hotbed of meth use when Hawaii’s epidemic first erupted in the mid-90s. The drug that continues to rip through a generation of families also ultimately led to Kipapa’s murder. He fought that, too — addiction — and it looked like he could have beat it if he wouldn’t have been murdered.

Percy was Waiāhole, the good and the bad. Likewise, Waiāhole is Hawaiʻi: the dispossession of Hawaiian people from their ancestral land; the unending Faustian drive toward “development;” the tension between economic and cultural pressures tugging you to leave and stay all at once; the creeping sense of hopelessness against impossibly large and faceless obstacles.

Kipapa’s life intersects and coincides with the major social and political forces at play in contemporary Hawaiʻi, and Mark Panek skillfully weaves deeply researched details into biographical narration, making Big Happiness a true-crime thriller and a vignette of change in Hawaiʻi.

Perhaps most impressive about the book, which was recognized as one of the 50 Essential Hawaii Books by Honolulu Magazine, is that even though Percy Kipapa’s life was large enough to reflect major forces shaping Hawaiʻi, Panek never lost the person in the subject matter. Big Happiness is a book about Hawaiʻi, but at its heart is a tragic story of a man who didn’t deserve to die, who represented all that’s best about Hawaiʻi. A man who could, and did, fight.

January Writing

For Civil Beat I wrote about staff shortages due to covid and how we can address it, as well as how teaching is (also) babysitting, and why that’s not an insult.

This newsletter is free, but if you like what you are reading and are feeling generous, here is a tip jar.